The Electronic Intifada Nahr al-Bared refugee camp 25 November 2014

Thousands of displaced Palestinians have yet to return to Nahr al-Bared refugee camp.

It was around 3am on 18 October when many Palestinian refugees on the outskirts of Nahr al-Bared camp in northern Lebanon were woken up by water flooding into the ground floors of their prefabricated homes.

That night, heavy rain had converted creeks into rivers, catching the refugees by surprise. For many, it was too late to remove their mattresses and furniture.

Ziyad Eshtawi narrowly managed to prevent the water from entering his home. He pointed at the poor foundation on which the temporary shelters stand.

“Back in 2008, the shelters were built in a hurry,” Eshtawi said. “The water doesn’t drain well.”

The 59-year-old has lived in a steel shelter for the past six years. His home used to stand inside Nahr al-Bared refugee camp, which was completely destroyed during fighting between a militant Jihadist group and the Lebanese army in the summer of 2007.

More than 30,000 Palestinians were forced to take refuge outside the camp during the fighting. Most of them later returned to its outskirts but the camp itself has not yet been fully rebuilt.

From doubt to hope

After the fighting, many refugees doubted that Nahr al-Bared would ever be rebuilt. After all, several Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon destroyed during the country’s fifteen-year-long civil war were never reconstructed.

Nevertheless, after various delays, reconstruction work in the camp finally started in 2009. “When the first buildings went up, we gained confidence that one day we would actually return to Nahr al-Bared,” Eshtawi recalled.

Eshtawi’s family expected to stay in the in the temporary housing for a maximum of two or three years. As stated in the preliminary master plan that was presented at the initial donor conference in Vienna in June 2008, the reconstruction of Nahr al-Bared could have been completed by 2011 in a best case scenario.

Yet Eshtawi and his family still live in the same white shelter at the northern edge of the camp.

A rebuilt school in Nahr al-Bared camp.

So far, slightly less than half of the camp has been rebuilt. Currently, reconstruction work in the fourth of eight sections is under way. Five of six school complexes have been built to date.

“Based on the funding that’s currently available, we estimate to have about half of the people back in there by the middle of next year,” Zizette Darkazally, who heads the Beirut communications and public information office of UNRWA, the UN agency for Palestine refugees, told The Electronic Intifada. The agency is undertaking the reconstruction of the camp.

Darkazally avoided mentioning concrete dates and timetables, as delays and work interruptions have occurred.

“Running out of funds”

The largest of all problems has been — and remains — funding. “We’re running out of funds,” said Darkazally, “We have received $188 million so far, and still need $157 million to finish the project.”

“We try to fundraise at any opportunity,” Darkazally stressed, claiming that Nahr al-Bared is a priority of both the Lebanese government and UNRWA.

However, the mammoth project has been heavily affected by the civil war in Syria and this year’s attacks by Israel in Gaza, as UNRWA was forced to adjust its services and fundraising efforts — and as many donors’ priorities have shifted elsewhere in the Middle East.

Switzerland, for example, which had contributed $1.7 million between 2008 and 2011, doesn’t plan to spend money on Nahr al-Bared again in the near future. Sonja Isella, spokesperson of the Swiss foreign ministry, told The Electronic Intifada, “Since the outbreak of the Syria crisis in 2011, we had to adjust our activities in the region.”

On 10 September, UNRWA organized a visit of donors to Nahr al-Bared, stating that if no more contributions were made, reconstruction would come to a halt next year.

Two months later, the shortfall of $157 million in the project budget remains unchanged.

Economic lifeline

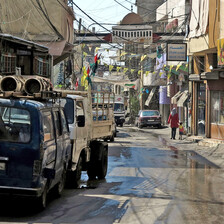

Meanwhile, the good news for Nahr al-Bared’s residents is that in December, the main street through the camp will be reopened. Before the war, the street had been the economic lifeline of the camp and a marketplace for the wider region in north Lebanon. When the camp was destroyed, all this changed.

After the fighting, the Lebanese army required a permit for visitors to enter the camp. As a result, Lebanese nationals were unable to enter it. The permit system was eventually lifted in October 2009.

Many shop owners expect that the opening of the main road will help the camp’s economy to grow.

UNRWA, the UN agency for Palestine refugees, says the camp’s main commercial street will reopen in December.

But in terms of the reconstruction timetable, no one in Nahr al-Bared has any illusions. Safaa Abbas, who works in a mobile phone shop, expects to live at least another three or four years in her tiny home on a hill in the south of the camp.

“My home is in section six,” she said. “But anyway, I don’t like how they rebuild the camp. It’s like a box of sardines and reminds me of an Israeli settlement.”

Indeed, the rebuilt buildings of Nahr al-Bared do not resemble the camp before the war. Gone are the Sasa, the Saffouri and the Safed neighborhoods named for their residents’ original towns and villages in Palestine.

The rebuilt areas of Nahr al-Bared lack this sense of identity. “It doesn’t mean much to me,” said Eshtawi. “Maybe I’ll get used to it one day, but my thoughts and memories remain in the old camp, where I grew up, spent most of my life and knew every corner,” he added.

“We hardly see each other”

Gone also are the camp’s zawareeb, or narrow alleys. In the new Nahr al-Bared, the streets are broader, there is more daylight and more air circulation. “That’s all good,” said Eshtawi’s daughter, Manal.

“However, when I sometimes go to Baddawi camp and walk through the zawareeb there, I feel at home. But here, between these new buildings, I really don’t.”

Her father explained that the displacement of Nahr al-Bared’s residents has torn the community apart.

“My brother and I had lived in the same home for more than forty years,” he explained. “Now, we hardly see each other, as we both ended up in different places.”

Eshtawi’s children have grown since the war — half of them now have their own families.

“I wonder where they’ll live,” he said, stressing that building on top of the rebuilt houses isn’t allowed and that most of the new homes are smaller than before.

Eshtawi’s home is in section five. “God knows when I’ll be able to return,” he said. “Unfortunately, it depends on so many things: the funding, the political situation in Lebanon and the wars in Syria and Iraq.”

After taking a sip of tea, he concluded: “Unfortunately, we live in a very bad political environment.”

Ray Smith is a freelance journalist and former activist with the anarchist media collective a-films, which documented post-war developments in Nahr al-Bared from 2007 to 2010.